Manspreading. Oversharing. Staring. Coffee-breath yawns. All are acceptable at home and often perpetrated in workplaces, but in the taut, increasingly crowded confines of a train we experience these kinds of behaviours far more intensely.

As cities grow more dense, culturally diverse and more congested, demand for public transport will continue to increase, as will our reliance on education campaigns to spell out what is considered good and bad behaviour.

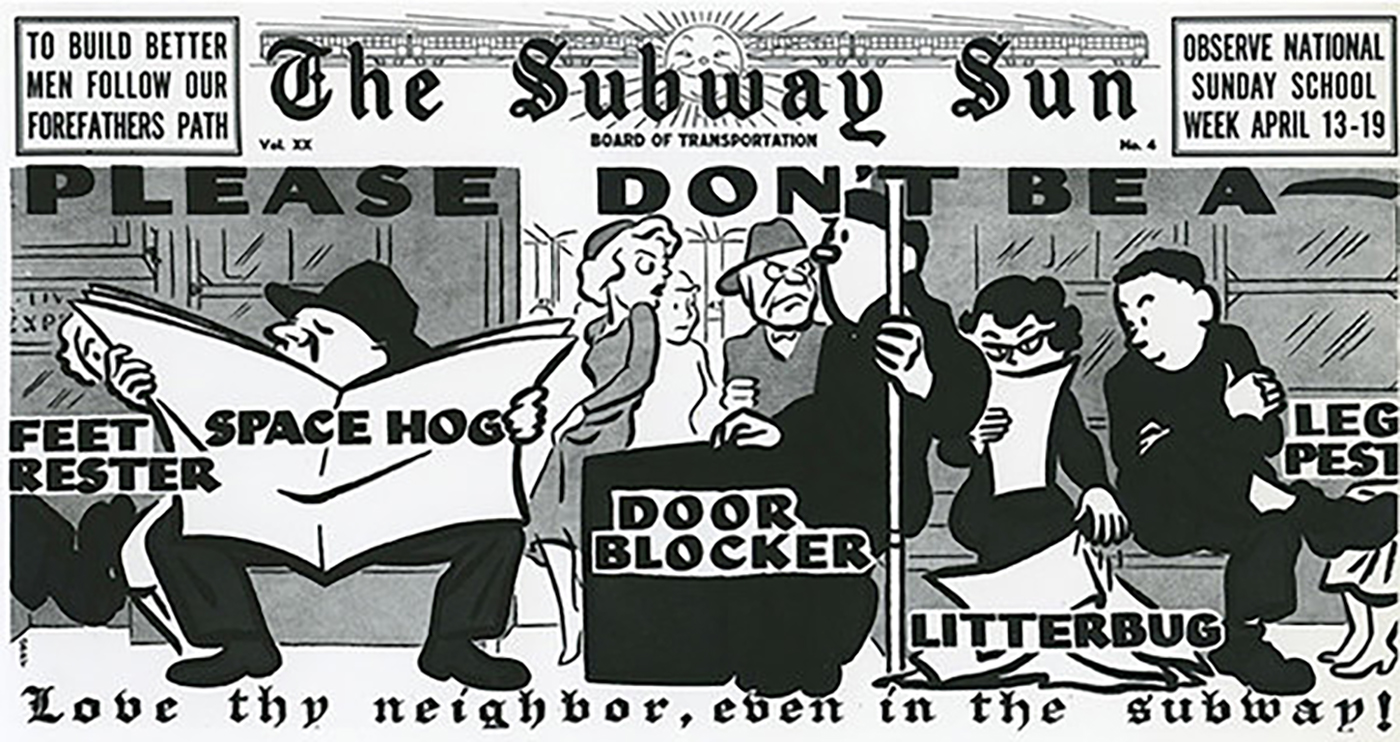

Subway etiquette campaign, early 1900s, New York Board of Transportation

Defining good and bad behaviour

Since 1854 when Australia’s first railway line opened in Victoria, public communication campaigns on train etiquette followed American and European trends by trying to convey a code of polite behaviour acceptable to a majority of passengers.

These campaigns imply and appeal to common values, from those universally seen as desirable – health and safety, comfort and personal space – to the more subjective end of the spectrum, like being nice and considering others. Antisocial behaviours like drinking alcohol can legally be classified as an offence; others that flout social customs are harder to police but can be just as intimidating for passengers.

Effectiveness of public etiquette campaigns

But do etiquette campaigns work? Research suggests they do, but they’re only part of the solution.

In a 2010 article from Transport Policy, Anglia Ruskin University author Stephen Moore advocates for the effectiveness of public awareness campaigns, citing research that shows passenger perceptions of the attractiveness of public transport were more likely to be impacted by low level antisocial behaviour such as talking loudly or eating food in close quarters. He notes that:

‘Rather than being tackled as a form of low level criminality, anti-social behaviour is viewed as the outcome of clashing values about appropriate behaviour on public transport.’

This approach of distinguishing between criminally antisocial behaviour that is policed according to the law and lower-level nuisance behaviours, which are largely the responsibility of each individual but can be influenced by social norms, has been pursued in many countries.

Campaign approaches and outcomes

In Victoria a fictitious lifecoach, Dr Merton, was flown in from the US in 2007 to school us on how to be better commuters. He was made to be loved or loathed and reactions to the campaign got people talking about public transport pet peeves such as mobile phones, personal space and hygiene.

Dr Merton train etiquette campaign, 2007, Connex, Melbourne

In New York, a campaign from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority using male/female icons was well received as a good mix of light-hearted and serious, with recommendations for making everyone’s journey a little better. (An affectionate video tribute by two local artists may have outshone the campaign but certainly helped spread its message online.)

A tribute to the subway etiquette campaign, 2015, artists CJ Koegel and Chris Zelig after the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, New York

Many etiquette campaigns tend to focus on exaggerated examples of bad behaviour to make a point, which can either make passengers self-discount because they’d never do such a thing – or worse: put them on the defensive because they feel insulted. This was the case with the Ride with Manners campaign in Hong Kong, which was widely criticised for blaming customers for etiquette shortcomings that some saw as largely a consequence of infrastructure underfunding.

Ride with Manners backpacker campaign, video still, 2017, Mass Transit Railway, Hong Kong

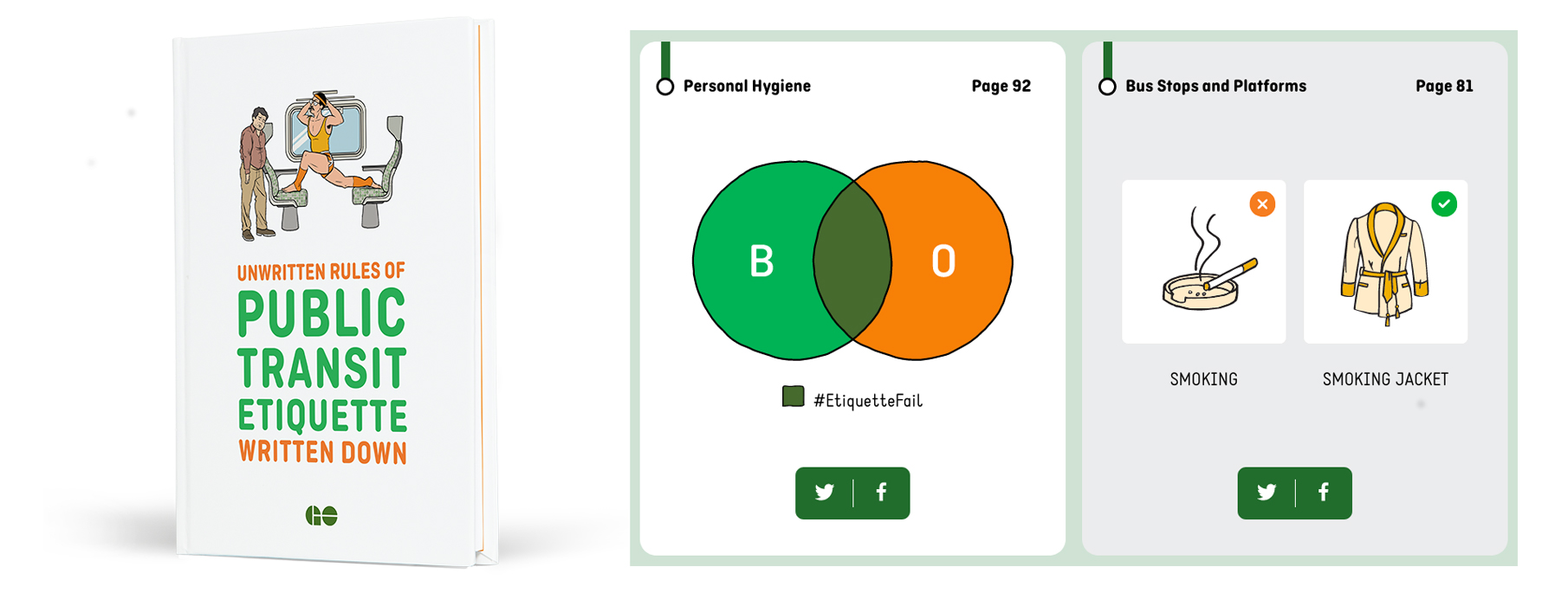

Conversely, showing good behaviours and hinting at the positive difference you can make in someone else’s day (and yours) would appeal to a basic sense of decency, a belief in good karma and our hardwired desire for community approval.

Public Transit etiquette campaign, 2018, excerpt from Unwritten Rules of Public Transit Etiquette Written Down, GO Transit, Canada

Onscreen messages, posters on station walls and inside trains all help reinforce the message. Other potential channels that could be used sparingly inside trains are LED screens to carry text and pre-recorded audio messages delivered over the PA system at peak times.

Ultimately, the ability to drive behaviour change through a heightened awareness of how to be a more considerate co-traveller is influenced by a host of other factors that are harder to get right: services running on time, being able to maintain culturally-appropriate personal space and trains that are clean and well presented. And as history shows, it’s an ongoing conversation we need to have.

By Alan Fitzpatrick