It’s Australia’s fastest growing chronic illness with more than one million people already diagnosed. Experts anticipate three million cases by 2025. Hearing these statistics, we tend to imagine the looming national spectre of cancer or heart disease – and with good reason: according to a recent World Health Organisation report cancer may have overtaken heart disease as Australia’s biggest killer.

But that’s one of the curious things about diabetes: until the symptoms become apparent it’s hard for health professionals to detect and harder for patients to recognise.

Through a combination of escalating prevalence figures and its links to other life threatening conditions, diabetes has earned its gruesome stripes. No cure exists and worse still, diabetes is extending its reach by stealth. Type 1 diabetes often appears at an early age, or is present at birth, and is controlled by daily insulin injections; type 2 can appear at any age, beginning with relatively minor symptoms like dizziness or lingering thirst: if left untreated, both types can lead to amputated limbs, blindness and death.

In the case of type 2, prevention has the potential to counter this grim vision. Diabetes Australia estimates that up to 58 per cent of type 2 diabetes cases could be prevented through healthier diet and exercise, and weight management. But it’s this change – breaking lifelong habits shaped by cultural and environmental influences – that’s often the hardest, particularly if people are not supported along the way.

A strategy to reach culturally diverse communities

Through our health promotion work for Diabetes Queensland for the National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS), we experienced this first hand. We were asked to create a strategy to tell patients and health professionals about the free support services available by signing up for the scheme and to investigate the issues that affect decisions about seeking help once a person has been diagnosed.

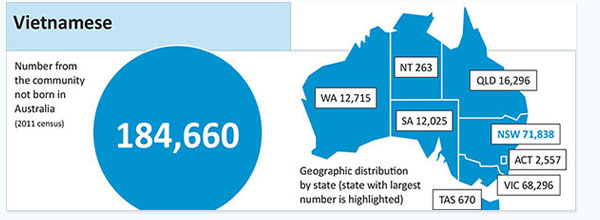

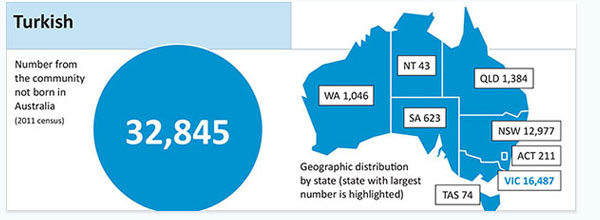

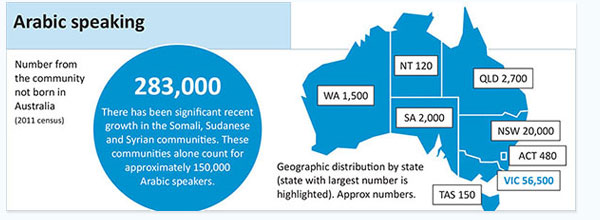

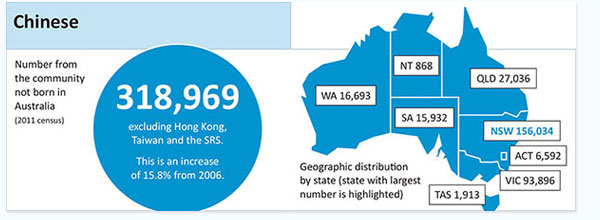

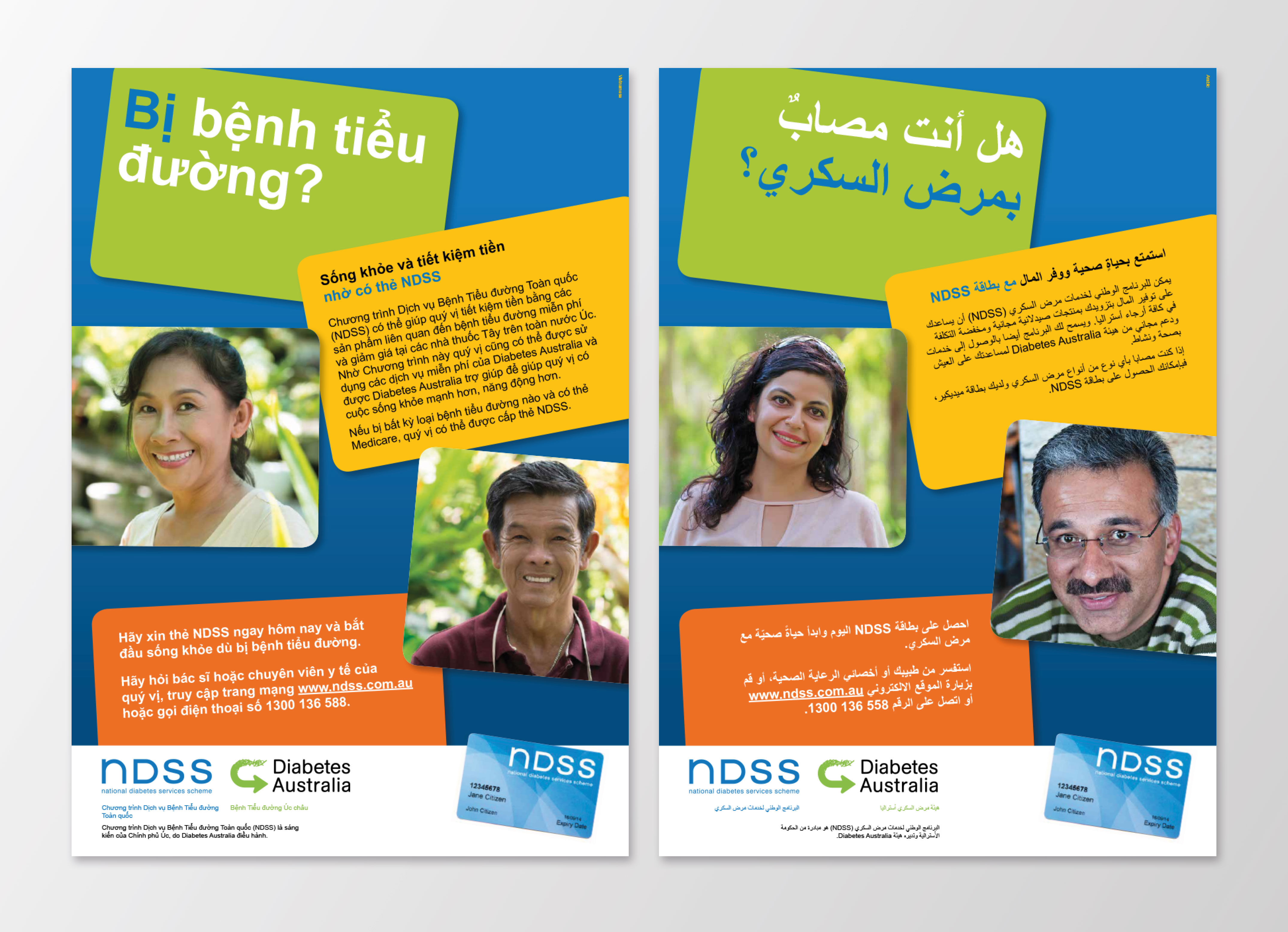

We spoke to people with diabetes from many walks of life and cultural backgrounds, as well as an array of health and allied health professionals. We identified language and literacy as major issues, and in response to these findings, developed translated resources and advertisements for media most often consumed by specific language groups including Chinese, Turkish, Arabic and Vietnamese.

Charts profiling four major language groups in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011 Census). Click images to view PDF versions with more detail.

The role of health professionals

Health professionals are a primary source of advice and can be influential in helping someone diagnosed with diabetes on the long journey to managing their illness and staying healthy. Like anyone in this situation, people from culturally diverse communities need good advice. But we also found that health professionals who showed cultural sensitivity were better placed to help people from diverse backgrounds come to terms with having diabetes and help them make informed decisions about whether to sign-up for a scheme such as the NDSS.

Our strategy to improve participation in the NDSS involved targeting information to help health professionals working with people from diverse cultural backgrounds, and increasing the number of languages covered by the scheme’s online multicultural portal of translated diabetes resources.

This mix of engaging health professionals to highlight the challenges multicultural groups with diabetes face, and raising awareness by targeting language groups with translated information about how the NDSS can help, will be key to increasing registrations.

By encouraging people get support to self-manage their diabetes we are also encouraging others to make lifestyle choices that could help prevent it by countering popular misperceptions about the illness. As the social stigma of diabetes slowly fades, support services such as the NDSS are instrumental to tackling the problem in Australia’s diverse communities.

By Alan Fitzpatrick and Madeleine Babiolakis